Amy Beach’s two most popular songs were recorded in 1911.

The narrative we tell about historical women composers is often one of recovery. Fanny Hensel is perfect for this—she only began to publish her music in her forties, then died young, so most of her output remained unavailable until the past few decades. Recently the music of African American composer Florence Price, some of whose manuscripts were found in an attic, has begun to receive well publicized and sometimes premiere performances. For International Women’s Day in 2018, the BBC ran a program highlighting the works of five women composers, playing up the “and their works have been hidden in archives for centuries” angle. We like our women composers to be “recovered” and to “break barriers”: the first woman to publish her madrigals, to write an opera, the first American woman to write a symphony, the first female winners of a Guggenheim or a Pulitzer. And we think somehow that if enough historic women are “rediscovered,” composers can break the canonic glass ceiling, overcome the obstacles to getting their music programmed, and that women’s secondary status in the concert hall will change.

Harmonic Club Program (1907), State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City

I’ve spent the last couple of years researching American women’s clubs involved in music. This summer I’ve enjoyed digging into the history of music clubs in my own state, Iowa. When I look at concert programs from a century ago what I notice is how many of them regularly feature women’s compositions. Take, for example, the Harmonic Club of Clinton, Iowa, which began in 1903 and lasted until 1945. Clinton was a transportation hub located on both the Mississippi River and railroad lines. It had about 23 thousand residents at the turn of the century, which was good-sized for a rural state. The Harmonic Club contained many local musicians, both men and women. I’ve seen Club programs from between 1907 and 1941 that contain music by women composers. There were entire programs dedicated to women, but these were written in up in the local press just as all the other programs were: the evenings of Beethoven, Mozart, or Mendelssohn, or the concerts of American music. Two major organizations encouraged clubs to study women composers, both the National Federation of Music Clubs and the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. But I don’t get the sense that the Harmonic Club was dutifully programming women purely due to these initiatives, as they performed women composers’ music frequently. Amy Beach, Guy d’Hardelot, Liza Lehman, Mary Turner Salter, Clara Kathleen Rogers, Harriet Ware, and Margaret Lang were likely to turn up, even on concerts with no stated theme; Cécile Chaminade figures more heavily in a French composers concert than she does in those dedicated to women.

Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s A Perfect Day (1910)

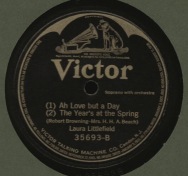

It strikes me that no one was making a big deal about how they were helping these women to break boundaries. In 1931, Mrs. Joseph Cahill gave the introductory report to the Club’s women composers program, commenting on women’s musical activity, which was “encouraged hesitatingly more than 200 years ago, but is now well patterned with creative effort.” In other words, in Clinton, Iowa, by the early twentieth century women composers were completely normal. When a chamber group from the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra appeared in Clinton in 1910, the soprano sang a Lied by Clara Schumann. The chapter of another women’s organization, the National League of American Pen Women, in Knoxville, Tennessee, programmed their members’ music for twenty years, beginning in the 1920s, performing the music of some seventy women. If you’d picked up a copy of Better Homes and Gardens in December 1925, you could have read how Amy Beach’s song, “The Year’s at the Spring” was a “best-seller.” Or you if saw the movie, Remember the Night when it came out in 1940, you’d discover that “everybody” could sing Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s “A Perfect Day.”

Yet here we are, recovering the women composers again, in spite of the fact that most of them have been here all along. I’m not underestimating the very real obstacles that women have faced, both in the past and today, and I’m grateful for genuine musicological “finds,” for Hensel’s Das Jahr and Price’s Piano Concerto. But I wonder if the way we shape the recovery narrative actually does more to hurt than to help. In heroically and repeatedly solving the problem by letting women in, we reinforce their outsider status, and there they stay, waiting for us to let them in again. The Clinton Harmonic Club should remind us that the problem is not that women composers were lost to history. If they aren’t getting performed now, the problem is us.